- Total

- General

- Arts

- Book

- Culture

- Economy

- Essay

- Fun/Joke

- History

- Hobbies

- Info

- Life

- Medical

- Movie

- Music

- Nature

- News

- Notice

- Opinion

- Philosophy

- Photo

- Poem

- Politics

- Science

- Sports

- Travel

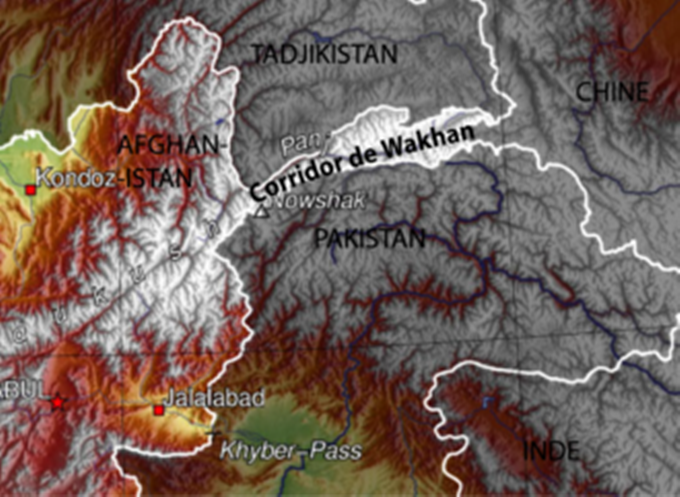

History Wakhan Corridor : 瓦罕走廊 : 와칸주랑

2021.09.25 05:37

Wakhan Corridor

Chinese

Simplified Chinese 瓦罕走廊

Traditional Chinese 瓦罕走廊

Literal Meaning Wakhan Corridor

The Wakhan Corridor (Pashto: واخان دهلېز, romanized: wāxān dahléz, Urdu: واخان راہداری Persian: دالان واخان, romanized: dâlân vâxân) is a narrow strip of territory in Afghanistan, extending to China and separating Tajikistan from Pakistan.

From this high mountain valley the Panj and Pamir rivers emerge and form the Amu Darya. A trade route through the valley has been used by travelers going to and from East, South, and Central Asia since antiquity.

The corridor was formed by an 1893 agreement between the British Empire (British India) and Afghanistan, creating the Durand Line. This narrow strip acted as a buffer zone between the Russian Empire and the British Empire (the regions of Russian Turkestan, now in Tajikistan, and the part of British India now in Pakistan and the contested region of Gilgit-Baltistan). Its eastern end bordered China's Xinjiang region, then ruled by the Qing dynasty.

Politically, the corridor is in the Wakhan District of Afghanistan's Badakhshan Province. As of 2010, the Wakhan Corridor had 12,000 inhabitants. The northern part of the Wakhan, populated by the Wakhi and Pamiri peoples, is also referred to as the Pamir.

The Wakhan Corridor forms the panhandle of Afghanistan's Badakhshan Province.

At its western entrance near the Afghan town of Ishkashim, the corridor is 18 km (11 mi) wide. The western third of the corridor varies from 13–30 km (8–19 mi) in width and widens to 65 km (40 mi) in the central Wakhan. At its eastern end, the corridor forks into two prongs that wrap around a salient of Chinese territory, forming the 92 km (57 mi) boundary between the two countries.

The Wakhjir Pass, which is the easternmost point on the southeastern prong, is about 300 km (190 mi) from Ishkashim.

The easternmost point of the northeastern prong is a nameless wilderness about 350 km (220 mi) from Ishkashim. On the Chinese side of the border is the Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

The northern border of the corridor is formed by the Pamir River and Lake Zorkul in the west and the high peaks of the Pamir Mountains in the east. To the north is Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region. To the south, the corridor is bounded by the high mountains of the Hindu Kush and Karakoram.

Along the southern flank of the corridor, there are two mountain passes that connect the corridor to its neighbors. The Broghol pass offers access to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region of Pakistan, while the Irshad Pass connects the corridor to Gilgit Baltistan. The Dilisang Pass, which also connects to Gilgit-Baltistan, is disused.

The easternmost pass, as indicated above, is the Wakhjir Pass, which connects to China and is the only border connection between that country and Afghanistan.

The corridor is higher in the east than in the west; (the Wakhjir Pass is 4,923 m (16,152 ft) in elevation) and descends to about 3,037 m (9,964 ft) at Ishkashim.

The Wakhjir River emerges from an ice cave on the Afghan side of the Wakhjir Pass and flows west, joining the Bozai Darya near the village of Bozai Gumbaz to form the Wakhan River. The Wakhan River then joins the Pamir River near Kala-i-Panj to form the Panj River, which then flows out of the Wakhan Corridor at Ishkashim.

The Chinese consider Chalachigu Valley, the valley east of Wakhjir Pass on the Chinese side connecting Taghdumbash Pamir, to be part of the Wakhan Corridor. The high mountain valley is about 100 km (60 mi) long. This valley, through which the Tashkurgan River flows, is generally about 3–5 km (2–3 mi) wide and less than 1 km (0.6 mi) at its narrowest point. This entire valley on the Chinese side is closed to visitors; however, local residents and herders from the area are permitted access.

In 1873 this corridor was created between the British Kingdom and Russian Empire already. And so it took several steps to complete this corridor between Afghanistan, China, and the others including Russian and Indian.

Although the terrain is extremely rugged, the Corridor was historically used as a trading route between Badakhshan and Yarkand. It appears that Marco Polo came this way.

The Portuguese Jesuit priest Bento de Goes crossed from the Wakhan to China between 1602 and 1606. In May 1906, Sir Aurel Stein explored the Wakhan and reported that at that time, 100 pony loads of goods crossed annually to China. There were further crossings in 1874 by Captain T.E. Gordon of the British Army, in 1891 by Francis Younghusband, and in 1894 by Lord Curzon.

Early travelers used one of three routes:

A northern route led up the valley of the Pamir River to Zorkul Lake, then east through the mountains to the valley of the Bartang River, then across the Sarikol Range to China.

A southern route led up the valley of the Wakhan River to the Wakhjir Pass to China. This pass is closed for at least five months a year and is only open irregularly for the remainder.

A central route branched off the southern route through the Little Pamir to the Murghab River valley.

The corridor is in part a political creation from The Great Game between the United Kingdom and Russian Empire.

In the north, an agreement between the empires in 1873 effectively split the historic region of Wakhan by making the Panj and Pamir Rivers the border between Afghanistan and the Russian Empire. In the south, the Durand Line agreement of 1893 marked the boundary between British India and Afghanistan. This left a narrow strip of land ruled by Afghanistan as a buffer between the two empires, which became known as the Wakhan Corridor in the 20th century.

The corridor has been closed to regular traffic for over a century and there is no modern road. There is a rough road from Ishkashim to Sarhad-e Broghil built in the 1960s, but only rough paths beyond. These paths run some 100 km (60 mi) from the road end to the Chinese border at Wakhjir Pass, and further to the far end of the Little Pamir.

Jacob Townsend has speculated on the possibility of drug smuggling from Afghanistan to China via the Wakhan Corridor and Wakhjir Pass but concluded that due to the difficulties of travel and border crossings, it would be minor compared to that conducted via Tajikistan's Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province or through Pakistan, both having much more accessible routes into China.

The remoteness of the region has meant that, despite the long-running wars of Afghanistan since the late 1970s, the region has remained virtually untouched by conflict and many locals, who are mostly composed of ethnic Pamir and Kyrgyz, are not aware of wars in the country.

The closure of the Afghan-Chinese border crossing at the Wakhjir Pass, on the east end of the Wakhan Corridor, has left the valley bereft of trade.

The government of Afghanistan has asked the People's Republic of China on several occasions to open the border in the Wakhan Corridor for economic reasons or as an alternative supply route for fighting the Taliban insurgency. The Chinese have resisted, largely due to unrest in its far western province of Xinjiang, which borders the corridor. In December 2009, it was reported that the United States had asked China to open the corridor.

Sandwiched between the mountains of the Hindu Kush and Karakoram, the Wakhan Corridor linking Afghanistan and China played a vital role in the 19th-century battle for control in Central Asia. Today, devoid of electricity and all extravagance, the Wakhan is a window into history centuries ago.

Text by Sophie Ibbotson & Max Lovell-Hoare.

"Walk On The Wild Side": The Wakhan Corridor.

There is a far, forgotten corner of Afghanistan where foreigners need not fear to tread. Some 100 years or so ago, this narrow sliver of territory, which juts out like a finger pointing straight at China, was central to the political and economic concerns not just of Afghanistan, but of the world.

It marked the meeting place of the Russian Empire and British India; the principal trade route from Central Asia to the Indian Subcontinent; and the hub of the so-called “Great Game”, where spies, explorers, and military officers danced in diplomatic shadows.

More than a century on, the Wakhan Corridor is all but neglected, and in terms of security at least, that’s a good thing.

The Soviet war in Afghanistan, between 1979 and 1989, left little behind, save some long-abandoned hardware, and the Taliban remained largely in their traditional heartlands in the country’s south.

Few people made the arduous journey on foot to the wildlands in the north. Now, only Wakhi and Kyrgyz nomads drive their flocks here, spurred on with the help of the Aga Khan, spiritual leader of the Ismaili community and, at least where rural schools and community centers are concerned, miracle workers.

We first came to the Wakhan in June 2010, taking a brief diversion into the valley while delivering aid vehicles from London to Faizabad, Badakhshan. This first glimpse set in motion a yearning to discover what lay beyond the cragged horizon, nestled betwixt the snow-capped Pamir and the Hindu Kush, and so a year later, we returned to follow in the footsteps of some of the 19th century’s greatest explorers.

These days, all journeys in the Wakhan begin in Ishkashim, the border town that straddles the Panj River (the Oxus of antiquity), a bridge linking Afghanistan with its northern neighbour, Tajikistan. Passes into China – which archaeologist and explorer Aurel Stein recorded 100 laden ponies crossing when he visited in 1906 – are now closed to foreigners, as is the way to Chitral in northern Pakistan.

Those on the Afghan side gaze longingly at the tarmac roads and twinkling lights of Tajikistan; car batteries and the occasional generator are the only sources of electricity here.

The Panj River is central to the Wakhan and its history. It has carved the valleys and irrigates the small patches of cultivated land along the valley floor. The search for the river’s source brought a succession of British explorers, Lord Curzon (later Viceroy of India), Lieutenant Colonel Sir Francis Younghusband, Lord Dunmore, Lieutenant John Wood, and Colonel Trotter amongst them. To walk in the wilds of the Wakhan is to walk in the footprints of history.

From Ishkashim, we drove our battered Land Rover to Sarhad-e Broghil, at the end of what passes for a road in the Wakhan. Constructed in the 1960s, it is a road in the very loosest of senses: traveling the little more than 80 kilometers along its length takes a full day of driving, broken dirt track interspersed with gravel riverbed and several river crossings. Even in September, when the rivers are low and the waters as yet unfrozen, it’s an exhausting, bone-shaking drive, though undoubtedly preferable to crossing the same terrain on foot.

The road, such as it is, peters to a halt at Sarhad, however, and from there on the only way is on foot. In his journal, Aurel Stein wrote, “Between Sarhad and the stage of Langar the valley contracts into a succession of defiles difficult for laden animals in the spring, when the winter route along the river bed is closed by the floodwater, while impracticable soft snow still covers the high summer-track.”

Nothing has changed at all. The narrow pathway – first across the 4,267-metre Daliz Pass, which we crossed panting and wheezing thanks to poor fitness and altitude, and then winding its way to the smattering of mud huts at Langar, used as rest stops by shepherds moving their flocks – clings to precipitous rock.

Though one or two wooden footbridges have been built, they scarcely look capable of taking a man’s weight, let alone that of a pony weighed down with packs. The days are bright, but there’s ice on the tents in the early morning, despite it being late summer, and even a smattering of snow now and then.

It’s not until the fourth day of walking that we see signs of permanent human habitation: a solitary yurt, a family, and their herd of yaks.

Life in the Wakhan is unbelievably tough – life expectancy is just 45 years – but the family is hospitable, welcoming us inside for steaming tea in porcelain bowls, sweetened with a little sugar, and large, flatbread that is softer if you dip it in the tea. Looking at their simple belongings, it’s hard not to think back to Curzon and his entourage who came here searching for ice caves in 1894.

They too carried everything with them, but unlike the modern traveller, Curzon felt it essential to carry his own collapsible rubber bath. Whether he was ever able to heat enough water to use it, however, remains one of Wakhan’s enduring mysteries!

We reached Bozai Gumbaz by mid-afternoon, the red dresses of the Kyrgyz women standing out strikingly against the greenish-grey of the surrounding landscape. This was where Francis Younghusband met the Russian Colonel Yanoff in the early 1890s, sharing champagne, caviar and three days of frivolity before sparking the so-called Pamir Incident and narrowly avoiding war. Our meals were far more meager pickings: dried fruits and nuts purchased in Khorog before leaving Tajikistan, army-style ration packs, and plenty of stodgy porridge.

Though the landscape and yurts remain unchanged, there is one important development here: in 2011, the Central Asia Institute built a school. Made famous in Greg Mortenson’s Stones into Schools, this is the first time that local children have had access to education. In three simple classrooms, teachers give lessons in Persian and English; the curriculum includes maths, sciences and literature.

The Wakhan Corridor may look more or less as it has done for centuries, but change is on the way. There is talk of a road to China and a reopening of the Broghil Pass to Pakistan. If you look closely, you’ll already spy occasional solar panels and mobile phones (albeit without network coverage).

The children, once educated, will ask for something more than eking out a life at the end of the world. If you want to see the Wakhan as a wilderness, now is the time to go. The world can change in a heartbeat, and once Wakhan’s potential is exploited, the traditional Wakhi way of life will quickly disappear.

Wakhan Corridor 2

Floodplains

Lake Victoria

Russian-Indian Border

Lianyun Fort - Wakhan Corridor: 여기서 Pech는 고대 연운보지역으로 추정한다.

ADDENDUM

1. Wakhan

Wakhan, or "the Wakhan" (also spelled Vakhan; Persian and Pashto: واخان, Vâxân, and Wāxān respectively; Tajik: Вахон, Vaxon), is a rugged, mountainous part of the Pamir, Hindu Kush and Karakoram regions of Afghanistan. Wakhan District is a district in Badakshan Province.

2. Wakhan District

Wakhan District is one of the 28 districts of Badakhshan Province in eastern Afghanistan. The total population for the district is about 13,000 residents. The district has three international borders: Tajikistan to the north, Pakistan to the south (specifically Gilgit-Baltistan and Chitral District), and the Chinese autonomous region of Xinjiang to the east. The capital of the district is the village of Khandud, which has a population of 1,244. It is the only district in Afghanistan that contains a population of Kyrgyz people.

3. Little Pamir

The Little Pamir (Wakhi: Wuch Pamir; Kyrgyz: Kichik Pamir; Persian: پامیر خرد, romanized: Pāmīr-e Chord)[1][2] is a broad U-shaped grassy valley or Pamir in the eastern part of the Wakhan in north-eastern Afghanistan. The valley is 100 km long and 10 km wide,[3] and is bounded to the north by the Nicholas Range, a subrange of the Pamir Mountains.

4. Great Pamir

The Great Pamir or Big Pamir (Wakhi: Past Pamir; Kyrgyz: Chang Pamir; Persian: پامیر کلان, romanized: Pāmīr-e Kalān) is a broad U-shaped grassy valley or Pamir in the eastern part of the Wakhan in north-eastern Afghanistan and the adjacent part of Tajikistan, in the Pamir Mountains. Zorko lake lies at the northern edge of the Great Pamir. The valley is 60 km long, and is bounded to the north by the Southern Alichur Range and to the south by the Nicholas Range and the Wakhan Range. The Great Pamir is used by Wakhi and Kyrgyz herders for summer pasture.] Side valleys support populations of Marco Polo sheep, snow leopard, ibex, and brown bear.

5. Wakhjir Pass

The Wakhjir Pass, also spelled Vakhjir Pass, is a mountain pass in the Hindu Kush or Pamirs at the eastern end of the Wakhan Corridor, the only potentially navigable pass between Afghanistan and China in the modern era. It links Wakhan in Afghanistan with the Tashkurgan Tajik Autonomous County in Xinjiang, China, at an altitude of 4,923 meters (16,152 ft), but the pass is not an official border crossing point. With a difference of 3.5 hours, the Afghanistan–China border has the sharpest official change of clocks of any international frontier (UTC+4:30 in Afghanistan to UTC+8, in China). China refers to the pass as South Wakhjir Pass (Chinese: 南瓦根基达坂), as there is a northern pass on the Chinese side.

6. Durand Line

The Durand Line (Pashto: د ډیورنډ کرښه; Urdu: ڈیورنڈ لائن) forms the Afghanistan–Pakistan border, a 2,670-kilometre (1,660 mi) international land border between the countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan in South Asia. The western end runs to the border with Iran and the eastern end to the border with India.

7. Mount Imeon

Mount Imeon (/ˈɪmiən/) is an ancient name for the Central Asian complex of mountain ranges comprising the present Hindu Kush, Pamir, and the Tian Shan, extending from the Zagros Mountains in the southwest to the Altay Mountains in the northeast, and linked to the Kunlun, Karakoram and Himalayas to the southeast.

Comment 3

-

What travel experiences you've had!

I've never been there. so I'm not familiar with those localities.

Let me try to figure out a few or some of them in Chinese.

1. Kunlun Shan : 崑崙山(곤륜산)

2. Hindu Kush : 興都庫什(흥도고십). an 800-kilometre-long (500 mi) mountain range in Central and South Asia to the west of the Himalayas that stretches from central Afghanistan into far northern Pakistan and far southern Tajikistan.

3. Karakorum : 喀喇崑崙山(객나곤륜산). Karakorum; Chinese: 哈拉和林) was the capital of the Mongol Empire between 1235 and 1260 and of the Northern Yuan in the 14–15th centuries.

4. Tian Shin Mountain : 天山(천산)

5. Alay Valley : 阿萊谷(아래곡) a broad, dry valley running east–west across most of southern Osh Province, Kyrgyzstan. It spreads over a length of 174 km east–west.

6. Bishkek-Osh : 比什凱克-奧什(비십개극-오십) the capital and largest city of Kyrgyzstan (Kyrgyz Republic).

7. Shangri-La : 香格里拉(향격리납) a fictional place described in the 1933 novel Lost Horizon by British author James Hilton. Hilton describes Shangri-La as a mystical, harmonious valley, gently guided from a lamasery, enclosed in the western end of the Kunlun Mountains.

8. Lost Horizon : 消失的地平線(소실적지평선)

9. Srinagar : 斯納加爾 the largest city and the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir.

10. Pamir mountains: 帕米爾(박미이) a mountain range between Central Asia, South Asia, and East Asia. It is located at a junction with other notable mountains, namely the Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun, Hindu Kush and the Himalaya mountain ranges. They are among the world's highest mountains.

Wow! I picked up some faintly familiar or totally unfamiliar nomenclature.

You don't make me even jealous since in my wild dream I shall not follow your footsteps.

I'll try to find some localities later.

Kwan Ho

-

This is my humble endeavor of China trip including

1. 西安(서안)

2. 天水(천수)

3. 蘭州(난주)

4. 嘉峪關(가욕관)

5. 楡林(유림)

6. Dunhuang; 敦煌

7. 陽 關(양관)

8. 烏魯木齊(우루무치)

9. 天池(천지)

10. 交河古城(Jiaohe Ruins)

11. Tulufan Shi(圖盧凡石: 투루판)

12. 秦始皇 兵馬俑(진시황 병마용)

13. 碑林(비림)

14. 楊貴妃華淸池(양귀비 화청지)

It wasn't too bad, but I want to go deeper to the west.

Kwan Ho

오늘은 Wakhan Corridor에 관하여 글을 올렸다.

요즘 고선지장군의 서역원정이 많이 소개되었고, 국내에서 시행한 연구재료도 많이 나왔다.

이번에 나는 Wikipedia에서 재료를 찾아 실었다.

그런데 고장군 당시 瓦罕走廊이란 용어는 물론 없었고, 현제 국제적으로 공인된 Wakhan Corridor 혹은 瓦罕走廊은 1800년도 후반에서 열강 즉 Russia, British Kingdom, India, Afghanistan 그리고 China등이 순차적으로 경계를 합의할 때 만들어진 용어이다.

나는 우리나라 소개에 "고선지 장군의 와칸 혈투"에 흥미를 갖고 소위 "The Battle of Wakhan Corridor"을 찾아보았지만, 그런 용어는 못찾았다.

분명히 고선지장군이 안서에서 와칸주랑을 지나 연운보 대전에서 승리하고 소발율등 여러나라를 항복받은 건 사실이지만 도대체 와칸은 어디고 연운보는 어디인가한 의문은 해답을 못 찾았다. 앞으로 국내 자료를 읽어 볼 계획이다.